Interview with Ilyse Iris Magy

Yosh Asato: You just returned from Portland where you attended XOXO, a conference celebrating art and technology. Lines Made by Walking, like Miguel Arzabe’s Sightlines, engages both digital and analog processes, yet the projects are very different. What is the role of technology in your work?

Ilyse Iris Magy: With Lines Made by Walking, I’m attempting to sort out and embrace my complicated relationship with technology, which has fundamentally shifted our relationship to maps and the city. I often wander for the sake of wandering, exploring new routes and relying on my strong mental map of the city to find my way. Yet it feels like I spend at least an hour a week on Google Maps, figuring out how to get from Point A to Point B with which transit mode and which route, in some strange effort to constantly optimize my commute. There is a lot of going back and forth from experiencing the city in the moment and looking at it from a satellite, essentially.

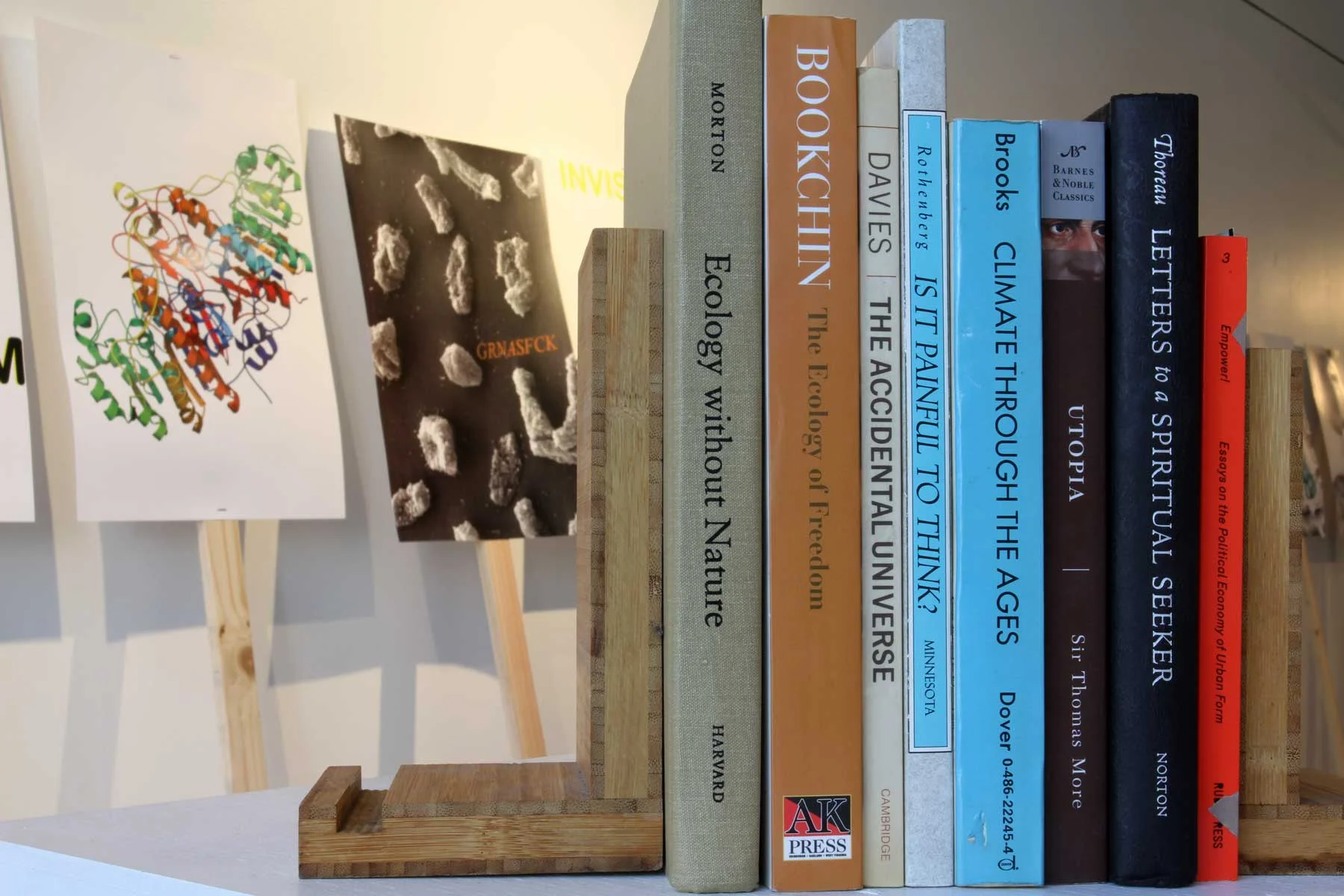

The five long walks and our means of tracking them are deliberately analog. We’ll use a paper map and physically mark points of interest we encounter on the ground with chalk. I composed all of the routes on foot. Yet I still used digital tools to tweak them afterward, and even made a website for the sake of sharing them. The base map projected onto the wall at StoreFrontLab is also digital; I created it using a program called TileMill. But the ultimate map is deliberately analog: once the projector is turned off, all that will be left on the wall are chalk marks and handwritten notes. Documenting this piece may also transform the analog map back into a digital, interactive one so that it can be experienced long after the show is over.

It is a dance back and forth between digital and analog, documentation and live experience, mark-making and the ephemeral. Tracking only certain reference points along the way means the lines made by our walks become the spaces between what we choose to document.

YA: Participation is a defining aspect of Lines Made by Walking. Why is having a group so important?

IIM: Participation is almost always a feature of my work, and thus a question in my practice. Lines Made by Walking in particular is study of the city, which is characterized by having so many relationships and interactions happening at once. Documenting a walk I take alone wouldn’t quite capture this multiplicity. On these upcoming walks, the content is emergent, and involving others increases the possibilities for interaction and discovery in a way that can better speak to a collective experience, though of course it is still subjective. The experience of deliberately walking in a group is also is part of what subverts the solitary nature of everyday walking.

YA: You’re also a cyclist who helped to organize the Sewer Ride earlier this year. Did you consider riding as a mode for mapping?

IIM: This piece is about relating your immediate surroundings to your position in the city as a whole. Walking was the clear choice. It’s matter of scale and speed. On a bike everything is rushing by; you are moving through the city instead of really dwelling in it. Walking creates more of a 1:1 relationship with your surroundings, a sense of intimacy. It is far more fluid to stop and investigate when you are on foot.

The slowness is really key. Walking long distances is a commitment, and intentionality changes your perspective on what you encounter. There is also something beautiful about the rhythm of walking, your steps merging and contributing to the rhythm of the city. That rhythm is so strong to me that I can never listen to music through headphones while moving through the city.

YA: You mentioned the mental map. How does the relationship between mapping and memory figure in your work?

IIM: In a sense, I’m poking at the relationship between our mental and corporeal experience of the city. We are constantly processing and filtering and distilling information. The things we encounter trigger associations that constitute the mental backdrop for our daily experience.

On these walks, when we notice or think of something, we’ll make a mark on the ground, a very physical gesture and a direct intervention into the landscape. How does this act affect how we relate to that point in space, as well as the mental connection it evoked? How does the mindset we occupy on these walks allow us to both engage with and sort through the many details that we otherwise ignore when we’re on a mission to get somewhere specific?

The points we mark may be familiar landmarks or they may be points that evoke a memory, but they will all be emergent. This simultaneously deliberate and arbitrary strategy subverts the traditional function of the map for wayfinding or data visualization and moves it closer to the realm of the narrative. It is documentation of an actual experience that cannot be relived, yet can be revisited and reinterpreted.

linesmadebywalking.com